Fairmont Gold Pieces, Part II: The Non-Pedigreed Fairmonts

/a guest blog by Richard Radick

Introduction: How I came to know and love the non-pedigreed Fairmonts

By August, 2020, when the first sale of Fairmont half eagles occurred, it had been apparent for some time that the coins of the “Fairmont Collection” were coming from a hoard, and a very large one, at that. Doug, for instance, had been saying this for a year or more.

A hoard is not a numismatic collection, in the usual sense of the word. The purpose of a hoard is to store wealth, and, often, to conceal it. While a numismatic collection may also serve this purpose, it is not the primary one. Most collectors probably tend to think of hoards mainly as important sources of supply. In this respect, I may be somewhat different - I regard hoards as fascinating subjects for study in their own right.

Unlike a collection, a coin hoard reflects the coinage readily available at the time and place of its formation. That place, of course, may not be where the hoard is eventually discovered; hoards can be moved, and there is certainly circumstantial evidence that the Fairmont hoard is one of these. It is also clear that the Fairmont hoard was assembled in 1932 or very shortly thereafter. It appears to be a representative sample of the gold coinage that was circulating in the US at that time.

Perhaps because they were the Fairmont coins currently being sold when I first became interested, or perhaps because I have an affinity for the series, I focused my attention on the Fairmont half eagles and, in particular, on those minted between 1834 and 1866. I will refer to these as the no-motto half eagles (NM $5s), because I include the Classic Head coins in the category, along with the no-motto Liberty Heads (the Classic Head coins, of course, also do not bear the motto: “In God We Trust”).

I decided to compile a database for the Fairmont NM $5s. I quickly realized that Fairmont coins have almost always been submitted to PCGS for certification and grading in large batches, sometimes numbering hundreds or even thousands of coins. Some of these batches have been date sets, but many of them comprise only a few date/mint varieties, and some have only one. Each batch ends up with sequential (or, at least, nearly sequential) PCGS Certification Numbers (“Certs”). Accordingly, once a Fairmont coin has been identified (from a Stack’s-Bowers sale catalog, for example), it is usually easy to find many more, simply by searching the nearby coins in the PCGS “Cert Verification” database.

By mid-2021, I had a database for the Fairmont NM $5s. Because the Fairmont Collection comes from a hoard, I expected to find larger numbers for the common-date (i.e., high mintage) issues among the NM $5s. In some cases, I did - the Philadelphia Classic Head issues (except the 1837), and some of the no-motto Liberty Head issues, such as 1844-O, 1845, 1846, and 1848, were, indeed, relatively plentiful. Many other common-date issues, however, were not - 1844, for example, was represented by only a single example (the one from the August, 2020, sale), and the high-mintage Philadelphia issues from the 1850s and 1861 were, similarly, also present in only small numbers. I decided these “missing” common-date coins would probably show up, sooner or later, so I began to monitor the PCGS Population Report numbers for the common-date NM $5s.

I did not have to wait long. In November, 2021, the PCGS Pop Report number for the 1853 $5 suddenly jumped by 145, from 455 to 600 coins. Aha! I thought, there they are! Now all I have to do is find the Certs.

And eventually I did, but I was dismayed to see that the coins were not Fairmonts - they did not have the pedigree. Then a light came on: Perhaps they *are* Fairmonts, I thought, but they simply have been graded without the pedigree. And then a second light came on: If the Fairmont 1853 $5s have been graded without the pedigree, then perhaps the other “missing” issues have been, also.

an example of an 1853 $5.00

It was time to construct some time series.

A time series is a record of repeated measurement of something that varies with time, with the time for each measurement recorded. Time series are encountered everywhere. The daily Dow Jones closing values are a time series. When you look at the graph of the PCGS Price History for a coin, you are looking at a time series. And so on, and so on…

I have dealt with the construction and analysis of time series throughout my career, so I was on very familiar ground. Furthermore, I realized that the numbers I needed to build the time series I wanted were available, because PCGS was publishing its current Pop Report numbers in its bi-monthly Rare Coin Market Report (RCMR) magazine.

eBay is wonderful. Provided it’s legal, there is someone on eBay ready to sell you almost anything you might want, including the back issues of the RCMR. I bought a set, and constructed the time series I wanted. Because the RCMR is published bi-monthly, the time series I built all have a two-month cadence, starting in late 2017.

In May, 2022, PCGS stopped including the Pop Report data, and well as its Price Guide numbers, in the RCMR, which, in my opinion, considerably diminishes the value of that publication. However, the current numbers are still available online, so I have been able to maintain my time series, up to the present.

In brief, jumps like the one I first noticed in the 1853 $5 population occur everywhere among the time series for PCGS-graded half eagles, starting in 2020, and are also common among the eagles and double eagles, starting a couple of years earlier. In contrast, they are nowhere to be seen among the gold dollars, the quarter eagles, or the $3s.

Furthermore, I have now tracked down the Certs connected with all the larger jumps among the NM $5s; some of these correspond to known batches of pedigreed Fairmonts, but most of them (like the 1853 $5 example) do not. There is, however, no longer any doubt in my mind that the latter cases (or, at least, most of them) also represent coins from the Fairmont hoard - they are what I now call the non-pedigreed Fairmonts. In total, there are thousands upon thousands of these coins, when all the half eagles, eagles, and double eagles are combined. Clearly, the non-pedigreed Fairmonts had been hiding in plain sight all along - I just didn’t recognize them as such, because they do not carry the Fairmont pedigree.

A Small Dose of Time Series Analysis

The figure below is the time series for the 1853 half eagles, shown as a simple bar chart with dates attached - 21-11, for example, is November, 2021. It should perhaps come as no surprise that I have selected this particular example for display, but it is also quite typical. The November, 2021, jump of 145 coins is clearly evident. There is also a second jump, considerably smaller, of 30 coins, that occurred six months later, in May, 2022. The jumps occur against a variable, but generally slowly rising, background - this background is simply the stream of 1853 half eagles that pass through PCGS grading all the time, and most of them are, undoubtedly, not Fairmont coins.

Thus, this time series presents one of the most common problems in time series analysis - the extraction of a signal (in this case, the jumps) from a variable (i.e., noisy) background. Of course, this background is always present, and it is present during the jumps, also. One cannot simply conclude, therefore, that the 145 and the 30 coins are all Fairmonts - some of them are from the non-Fairmont background, and that number must be estimated and removed.

Complicating matters still further, there are some 1853 half eagles that are known to be Fairmonts (the few pedigreed Fairmonts, in particular) that are not included in the two jumps - they are, instead, hidden by the background, and need to be included in the total. Another way to look at this is: a single 1853 in a large date run of Fairmont half eagles will show up as a tiny extra increment in the 1853 time series, which is impossible to separate from the varying background, except statistically.

As should be fairly evident by this point, the analysis can become rather messy. The bottom line is that it is impossible to extract an exact number for the signal (i.e., the number of Fairmonts) from a noisy time series like this - the best one can hope for is an estimate, hopefully a fairly good one. For the 1853 $5s, that estimate turns out to be 177 coins (pedigreed plus non-pedigreed Fairmonts, combined), and it is probably accurate to about ±10 coins.

The figure below is another time series, this one for the 1861 $5s. Like the one for the 1853 half eagles, it also features a prominent upward jump, this one for 725 coins graded in January, 2021. I noticed this jump when I first constructed the time series for the 1861 half eagles in early 2022.

I decided to track down the PCGS Certs for these 725 coins, because I had set the goal of finding the Certs for all the Fairmont NM $5s, pedigreed & non-pedigreed. I found Certs for 695 1861 $5s, graded as seven single-date batches of about 100 coins each, all non-pedigreed. The numerical gaps between the seven sequences are short, so there can be little doubt that the coins were all graded at about the same time, and the specific Cert numbers point to early 2021 - they are undoubtedly the “jump” coins.

Embedded within the seven sequences were 26 numbers that returned the PCGS Invalid Cert message - whether these numbers had ever corresponded to actual coins is, of course, unclear. Experience has shown that there are occasionally gaps in PCGS Cert number sequences, even for newly-graded PCGS coins, and perhaps these missing numbers correspond to Certs that were spoiled in some way during the grading process, or to some other clerical error in PCGS’s Cert management system. Or, perhaps the 26 missing Certs corresponded to coins that had been removed from the PCGS database at some point between early 2021 (when the coins were graded) and early 2022 (when I made my list), as cross-overs or re-grades.

Assuming the 26 invalid Certs corresponded to actual coins at one time, the implied total was 695 + 26 = 721. The remaining four coins (725 - 721) were presumably non-Fairmonts (i.e., background coins) that just happened to be graded at the same time as the non-pedigreed Fairmonts.

In May, 2022, another jump in the PCGS Pop Report number for the 1861 $5s occurred, but this one was downward - the total was reduced by 193 coins. It is not unusual to find reductions of a few coins in the individual time series, which probably indicate cross-over coins or re-grades, but a downward jump of 193 coins is remarkable. At the time, I filed this in my “Interesting - perhaps someday I will look into it further” box.

That day finally arrived after I realized recently that the large downward jump in the 1861 $5 time series is not a one-off, but has happened for several other issues as well.

I decided to re-examine my 2022 list of the 1861 $5s, and discovered that it now contains 214 additional Invalid Cert entries, along with the 26 I had noted in early 2022. Unlike the 26 examples from 2022, however, there can be no doubt that the 214 more recent missing numbers had all been, at one time, assigned to Certs that correspond to actual coins - I have a list of those coins, after all. However, between early 2022 and today, they have become “ghost” coins - coins that no longer exist as valid PCGS-graded coins. There is little doubt in my mind that the reduction of 193 coins that PCGS reported in May, 2022, accounts for most of these 214 ghost coins - there is, really, no other possibility. Evidently, Fairmonts can become ghost coins, and it may happen rather often.

Precisely what happened to these ghost Fairmonts is not clear. Perhaps they were sent elsewhere (to NGC, most likely) as crack-outs or cross-overs. There is no evidence in the PCGS time series that they remained with PCGS, so they probably were not simply re-grades that received new Cert numbers. In any case, PCGS evidently knows that something happened to these ghost coins, because they adjusted the Pop Report numbers.

If anyone has ever wondered whether there are Fairmont coins graded by NGC, the answer is: yes, there probably are, and perhaps quite a few of them, but they are likely crack-outs or cross-overs, and most (if not all) were once non-pedigreed Fairmonts. Perhaps someday a pedigreed Fairmont will show up in an NGC holder, but, so far, I have not seen any.

At the end of all this, I arrived an estimate of 750 for the total number of 1861 Fairmont half eagles, again with a likely error of perhaps ±10 coins, or maybe somewhat larger.

A couple concluding points:

(1) I believe that most of the jumps that occur in my time series are caused by Fairmont coins, with a few of them corresponding to pedigreed coins, but most of them corresponding to non-pedigreed Fairmonts. However, not all jumps involve Fairmonts. For example, the time series for the 1857 (and a year or so prior) San Francisco eagles and double eagles show jumps in 2018 that are undoubtedly the signature of coins from the S.S. Central America treasure that were graded by PCGS at that time. There are probably other instances like this, of which I remain unaware.

(2) The best I can obtain from any individual time series is an estimate for the total number of Fairmont coins, pedigreed and non-pedigreed combined, that have been graded by PCGS between late 2017 and the present, and not an exact count. Like any estimate, it is inherently imprecise. I believe this uncertainly to be about ±10 coins, perhaps a bit fewer for the scarcer issues, and more for the common dates, for which literally thousands of (mainly non-pedigreed) Fairmont coins sometimes exist. I may work on quantifying this uncertainty more exactly in the future.

Results: Estimates for the Total Number of Fairmont Coins, by Denomination and Mint

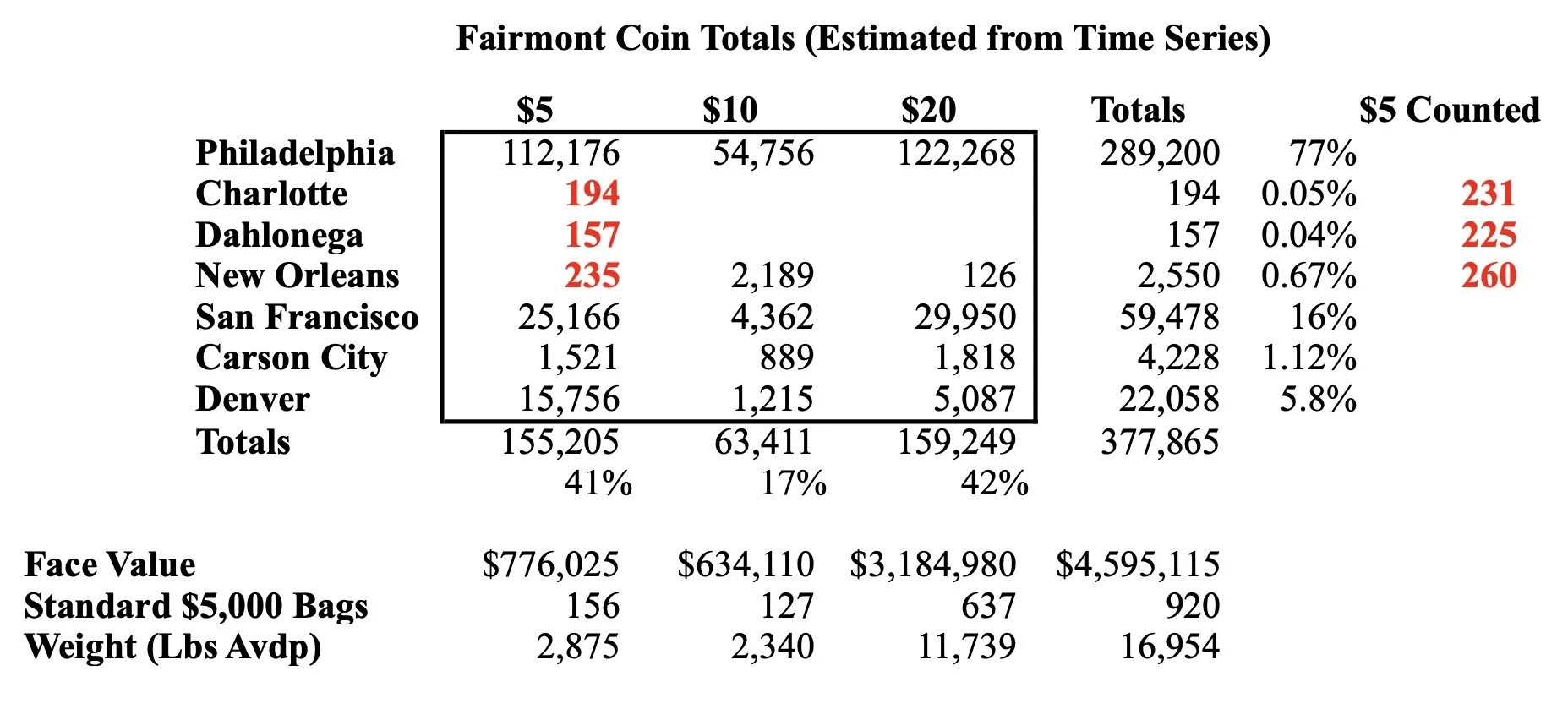

The table below presents the results. At the foot of the table are three lines that convey a sense of the enormous size of Fairmont hoard: the face value of the coins, the number of the standard $5,000-face bags of the day that were required to store them (each filled bag weighing about 18-1/2 lbs), and the total weight. In view of the fact that the known size of the hoard continues to grow, it might not be too inaccurate to say that the Fairmont hoard comprises perhaps 1,000 standard bags of gold coins, and weighs about 9 tons.

A few concluding observations:

(1) The Fairmont hoard is evidently truly enormous, comprising almost 380,000 coins, according to the current estimates developed here. And this is not the final number: Fairmont coins are still being submitted to PCGS for grading at the present time (late 2023). Furthermore, the estimates above also do not include any worn or damaged coins from the Fairmont hoard that will never be graded, because they are not deemed worth the expense. They also do not include any Fairmont coins that have received PCGS-Details grades - such coins are not included in the PCGS Pop Reports.

(2) Philadelphia coins make up 76% of the total; coins from San Francisco account for only 16%. The ratio is about 4.75:1. However, the original mintage ratio is considerably closer, about 1.4:1. This may be telling us that the Fairmont hoard was originally assembled on the East Coast; had it been formed on the West Coast, it seems plausible that the imbalance between Philadelphia coins and San Francisco coins would be considerably smaller.

(3) The numbers highlighted in red provide an indication of the ability of the procedure I have developed to extract small numbers from the time series. The far right-hand column labeled “$5 Counted” contains my actual counts of Fairmont half eagles with PCGS numerical grades from the three Southern mints, highlighted in red. The corresponding estimates are similarly highlighted in the main body of the table. Combined, these issues account for only a tiny fraction of the entire Fairmont hoard - less that 0.2%. Even so, the estimates are clearly not totally crazy. Given that the numbers for the Southern half eagles in the PCGS Pop Reports are likely to be distorted by unrecognized re-grades and crack-outs, I think the performance of the algorithm is quite good.

(4) There are clearly some series that may be vulnerable to being “Fairmonted,” to borrow Doug’s term. For example, if you have been stuffing your investment portfolio with run-of-the-mill Carson City gold coins or New Orleans eagles, you might want to reconsider your strategy. On the other hand, if you favor half eagles from Charlotte or Dahlonega, the risk seems likely to be minimal. I suppose a large number of these coins could still emerge from the Fairmont hoard in the future, but I now think that possibility is rather remote.